Waheed Murad (October 2, 1938 – November 23, 1983) is one of the greatest icons of the culture of Pakistan. In his lifetime, he owed his legendary status mainly to his unprecedented appeal as a filmstar. Since 2008, his legacy as a writer, producer and director of movies has also been receiving attention.

Waheed produced 11 movies under his banner Film Arts. He wrote four of these, and one was also directed by him. He acted in a total of 124 movies, including two posthumous releases (the figure does not include a few cameo appearances and some unfinished projects).

The active years of his career were from 1960 till his death in 1983. In his lifetime, he received several prestigious awards, including Nigar, Graduate, PIA Academy and others. His posthumous accolades include a Nigar for Lifetime Achievement in 2002 and Sitara-e-Imtiaz in 2011.

Personal Life

Waheed Murad was born on October 2, 1938, in Karachi, to Nisar and Shirin Murad. On the paternal side, he descended from a family that was once near royalty in the Bahmani kingdom of South India, perhaps up to the downfall of the kingdom in the 1520s. The family then migrated to Kashmir on the invitation of the ruler of that state, and came to be known as the ‘New Bahmani’ family. When mass migrations started from the state in the late 18th century, the family or at least some of its members migrated to Sialkot. The surname ‘Murad’ was adopted in 1887, at the time of Waheed’s grandfather Zahur Ilahi Murad. Zahoor’s brother was also named Ferozuddin Murad, and became famous as F. D. Murad, head of the Department of Physics at the Aligarh Muslim University (India), where a gold metal is still awarded in his name every year.

Zahoor’s teacher in his early years was Maulvi Syed Mir Hasan, best remembered as the teacher of Allama Iqbal (ten years older than Zahoor and almost certainly a close acquaintance, since they grew up in neighbouring streets in addition to having the same teacher). An article Zahoor wrote on the death of his teacher in 1929 is perhaps his only writing that exists today. By profession, Zahoor was an advocate but took an active part in social activism, especially in the service of Anjuman Himayat-i-Islam.

Nisar Murad (1915-1982) was the second youngest son of Zahoor. He migrated to Bombay (now Mumbai) in search of a lucrative career, finding it in the business of film distribution and marrying a Christian woman from Bikanir, who converted to Islam and was renamed Shireen. Sometime later the couple migrated to Karachi. Waheed was born there and was their only child.

The schooling of Waheed started at Lawrence College, Murree, one of the most prestigious institutions in British India (he must have lived in the boarding house, like most other students). He could only study there for two years because his parents missed him too much. He was then admitted to Mary Colaco School in Karachi (‘Colaco’ is pronounced ‘Colasso’). In 1954, he passed the High School Final Examination (Grade 10, or ‘Matriculation’), with Arabic and Additional English as optional subjects, and distinction in Physics and Chemistry. He passed the Intermediate from S. M. Science College, and Bachelor of Arts (B.A.) from S. M. Arts College.

He got admission in the University of California, Los Angeles, for studying filmmaking but his parents did not want to part with their only child. His father suggested that he should study filmmaking through hands-on experience by setting up his own production house, and completing masters as an external candidate from Karachi University. The exam was held in May 1962, which he passed in second division according to the degree issued on May 17, 1963.

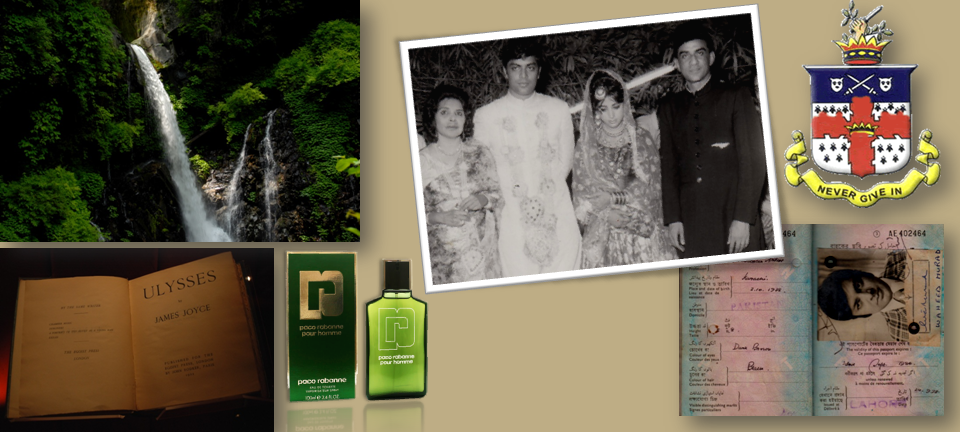

He married Salma Maker on September 17, 1964. Salma’s father, H. E. Maker, owned H. M. Silk Mills. Waheed and Salma had three children. The eldest, Aliya, was born in Karachi on December 23, 1969. The second, Saadia, also born in Karachi and died in infancy. The youngest, Adil, was born in Lahore on November 13, 1976, and later made a career in media production.

Waheed’s parents were living in an apartment opposite Light House Cinema on M. A. Jinnah Road, Karachi, while he was growing up. They later moved to 231-C, Block 2, P.E.C.H. Society and were their at least till April 1965. Some afterwards, they moved to 158-R, Block 2, P.E.C.H. Society on Tariq Road. In 1973, Waheed shifte to Lahore and took residence at 72-G, Gulberg III. He named his house ‘Qasr-i-Armaan’ after his most famous movie.

He was 5′ 8″ tall with dark brown eyes and black hair, as mentioned in his passport. His favourite perfume was Paco Rabbanne, Pour Homme (introduced by Jean Martel in 1973). His closest friends called him ‘Wido’ (pronounced ‘Veedu’), but they were few. He was an exceptionally reserved person in real life (in stark contrast to his personality on screen).

He was extremely fond of reading and collecting books. According to Javid Ali Khan, Waheed’s friend from the student days, he became especially impressed by James Joyce’s Ulysses, and subsequently tried to read all the masters of the stream of consciousness method of storytelling, such as Henry James, Virginia Woolfe and William Faulkner. His favourites also included The Turn of the Screw by Henry James, which eventually became source material for the movie Mehman by Waheed’s former classfellow and colleague Pervez Malik (although Waheed did not appear in that movie).

Playing cricket was also another favorite passtime. He also participated in several matches on behalf of the film industry in his peak years.

He also became extremely devoted to Lal Shahbaz Qalandar, a thirteenth-century saint and scholar from the city of Marwand (Iran) buried in Sehwan (Pakistan). It started with a visit to the shrine under unusual circumstances in 1962. He then became a regular visitor to the shrine until he found himself become a distraction for the visitors due to his celebrity status and stopped visiting the place in 1966, out of sheer respect for the memory of the saint. He stayed in touch with the custodians of the shrine and continued to pay homage by sending at least a ceremonial sheet of flowers every year on the occasion of the annual festival.

Outside Pakistan, he developed an extraordinary fascination for Japan, when he visited the country in July 1970 for the shooting of his movie, Khamosh Nigahain, as discernible from the letters he wrote to Salma during that trip (reproduced in Waheed Murad: His Life and Our Times), e.g.:

Today I had a wonderful experience. We left early in the morning for a place called Nikko – the train journey took us out of Tokyo which is a jungle of buildings into the countryside and the change has to [be] seen to be believed. The countryside is green and so simple looking – almost like Pakistan – Eventually we are at a hill station called Nikko which has a little station and a cute little town a bit like Chamonix, and a huge lake – more uncluttered and serene than the lakes in Geneva. And then there was the waterfall a huge, high torrent which roared so loud we couldn’t hear ourselves speak – we started a song there but after a while such thick fog came down that the taxi literally crawled back to the station. Not much work done but a day made pleasant & satisfying by the sheer beauty of the place.

‘Film Producer Artist’ is how he described his occupation in his passport. His ‘active years’ in the film trade could be mentioned as 1960 to 1983, i.e. from setting up his banner Film Arts till his death. Practically, however, he had started earlier than that by unofficially assisting in his father’s business of film distribution. Also, two of his movies were released posthumously, in 1985 and 1987.

He received a major setback when his father fell ill, passing away in June 1982. Soon afterwards, Waheed himself fell ill. He had already undergone surgery for appendicitis in September 1980. In the summer of 1982, he developed ulcer problems. On January 2, 1983, his ulcer burst and a part of his stomach had to be removed. Later, in September, he had an accident while driving in Lahore. It left a scar on his face. Arrangements for plastic surgery were still being made when he passed away in a friend’s house in Karachi, in the early hours of November 23. The cause of death was cardiac arrest.

His son Adil was with him at that time while his wife Salma and daughter Aliya were away on a trip to the US, visiting some relatives.

During the last years of his life, film trade in Pakistan was hitting rockbottom so that those years could have been described as the worst phase in the career and life of almost anybody linked with the industry. Yet, his face alone became the icon of this phenomenon. The downfall of the film trade in Pakistan in the early 1980s was often dubbed as ‘the downfall of Waheed Murad’, in spite of his public denials that anything was wrong with him except health problems and their inevitable effect on his career.

Against this backdrop, the society received the news of his death not only with disbelief, shock and grief but also remorse, if not collective guilt. President General Ziaul Haque sent condolence message to Salma, the state-owned television broadcast a special program and while the official acknowledgement ended there, the public response was a different story. As recounted in Waheed Murad: His Life and Our Times (2015):

The next year, 1984, passed like a year of mourning. Almost the entire repertoire of his movies was brought back to cinemas, and the advertisements usually appeared like obituaries.

In addition to special issues of magazines and newspapers, there were also books that came out with titles like Who Killed Waheed Murad? (Waheed Murad Ka Qatil Kaun?). Special audio cassettes of his songs came out with passionate commentaries that could move many listeners to tears, and they often did. In those days, it may have been difficult to walk across a city centre in Pakistan without hearing a song of Waheed, or one of those audio-recorded obituaries.

In cinemas where his old movies were re-released, his fans provided commemorative posters and decorated the foyers with more ‘fanfare’ than premieres of new movies were getting at that time. In those foyers, people wept without feeling embarrassed about it. Strangers from diverse social backgrounds were seen sharing their feelings about the dead artist unreservedly.

Thirteen months of mourning ended with the posthumous release of Waheed’s last production, Hero, on January 11, 1985. Tears were shed again, but a catharsis was also found – and a sense of relief that the movie, initially abandoned after his death, had finally been completed ‘on popular demand’.

In the meanwhile, a cult had been born. His first death anniversary was observed by his fans with recitals of the Quran, and prayers for his soul. This has been happening across the country every year since then.

Controversies surrounding a celebrity are important to his or her biography but the case of Waheed is peculiar in this respect. Unlike many other celebrities, he did not come out in public to address the issues that were being linked with him.

Perhaps the most frequently raised ‘allegation’ in his lifetime was that he was arrogant. A journalist once asked him about it. He replied by politely asking the interviewer, ‘Have I ever misbehaved with you or any other journalist?’ When asked in the TV show Silver Jubilee (1983) why certain female leads had refused to work with him in the past, he replied that in all fairness the question should be addressed to them and not him. In an interview for a popular magazine a little earlier he had furiously denied that he was having any trouble in his marriage.

The more sinister suggestion appearing in the Wikipedia article (retrieved on Novermber 18, 2016) that his death might have been suicide, has no basis in fact and is implausible even as pure speculation.

Filmmaker

Waheed started his production house by the name of Film Arts in 1960, and produced a total of eleven movies under that banner. The first two can be treated as pilot projects (he was still a student and did not act in them): Insaan Badalta Hai (1961) and Jabse Dekha Hai Tumhen (1963). He acted in all other nine productions: Heera Aur Patther (1964);

;

Armaan (1966); Ehsaan (1967); Samandar (1968); Ishara (1969); Naseeb Apna Apna (1970); Mastana Mahi (Punjabi; 1971); Jaal (1973) and Hero (posthumously released in 1985).

He also co-produced another movie, Maa Beta (1969), but not under his banner.

His decision to have a career in movies is said to have been prompted by two factors. The first of these has been mentioned by his childhood friend, Javid Ali Khan, ‘We grew up with a mind to serve the nation just the way the Quaid-i-Azam and Quaid-i-Millat Liaquat Ali Khan had asked us to. Waheed believed that he could do this through movies.’ His wife Salma says that whenever he started producing a new movie, she would hear him say, ‘I have got a message to deliver.’

The second factor has been mentioned by another childhood friend, Pervez Malik. He writes that since Nisar Murad was a successful film distributor, there was an atmosphere of movies even at Waheed’s home. ‘Film celebrities were given receptions at his place on their visits to Karachi,’ Malik writes, ‘All of us friends also attended such receptions, and it was here at the house of Waheed that I saw the famous film stars of those days, which included Santosh Kumar, Sabiha Khanum, Shamim Ara, Ala-ud-din, Talish and many others. Besides, whenever Nisar Murad took a film for distribution, he first arranged its viewing at his home, in which we all participated. Then it was discussed. We would all give our comments and make predictions about the success or failure of the film.’ According to Malik, this atmosphere evoked in him and Waheed a passion for cinema.

His personality as a film producer has been summed up in Waheed Murad: His Life and Our Times (2015) as follows:

He came out as a thorough businessman from the very start. Film trade never gained the status of an industry in Pakistan during his lifetime. As such, films could not be insured. Producers were notorious for withholding payments, especially of the lower staff but sometimes also of the minor stars. Some, especially newcomers, squandered away their budgets on extracurricular activities and left the project unfinished. Waheed entered the business as one of those few who were miles apart from this culture. In monetary matters he was tight-fisted like a cool-headed businessman but was also extremely honest, upright and reliable. Payments were made out by him without reminders, and he extended professional respect even to the lower staff. Other than this he was aloof and shy to the point of being mistaken as arrogant. The comedian Lehri described him aptly as ‘a to-the-point man, well-educated and noble’.

According to Pervez Malik, ‘he took personal interest in every department of film. His opinion would be reflected in everything – story, music, set, wardrobe, and so on.’ In the words of Sohail Rana, ‘He was a complete film personality – producer, actor, director and writer.’

He was the youngest film producer in the country when he released his first movie (he was twenty-two). In his lifetime, however, this aspect of his work was not celebrated as much as his presence as an actor. He received only three awards for production, all for Armaan: Nigar Award, Rooman Award and Noor Jahan Award.

As a producer, he also became famous as the man who succeeded in building a team of four educated, sophisticated and extremely patriotic young men: he as producer, writer and actor; Sohail Rana as music composer; Masroor Anwar as poet; and Pervez Malik as director. The four worked together on Heera Aur Pather, Armaan and Ehsaan under the banner of Film Arts. Apart from these three movies, all four names came together only in two others: Doraha (1967) and Usey Dekha Usey Chaha (1974). Those two movies could not be very successful, and Waheed later blamed Doraha for the breakup of the team.

It is also interesting to see that most artists whom Waheed ever brought under his banner were religiously-inclined in some sense, intensely patriotic and completely free of that skepticism about the rationale of Pakistan that has always been so common among the intellectuals of the country. Some of the names, in addition to the three already mentioned, are Munawar Rashid (pronounced ‘Rasheed’), Syed Iqbal Hussain Rizvi, Himayat Ali Shair, Sehba Akhtar, Zahoor Ahmad and Azad (the former driver of the Quaid-i-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah).

Waheed also directed a movie. This was Ishara, also written and produced by him. In addition to acting in it he also sang an uncredited playback song with the co-star Deeba. The movie completed more than 25 cumulative weeks at the box office (‘Silver Jubilee’). By the standards of that time it did not mean a great success but it was not a box office bomb or flop either. Purely from a directorial point of view, however, the movie appears to be a deliberate attempt to showcase the best practices of the indigenous cinema of the age.

Writer

Waheed wrote Armaan (1966), Ishara (1969) and Hero (1985). Some websites mention him also as the author of Ehsaan (1967) but this is not correct. The credits of that movie name Masroor Anwar for story, lyrics and dialogue. Mushtaq Gazdar was also wrong when he wrote in Pakistan Cinema (1997) that Waheed was credited for the story of Samandar (1968). Not only the credits of the movie but even the official poster mentions Agha Nazir Kawish as the writer, not Waheed.

The three stories written by Waheed, then, are his contribution to Urdu literature, the true worth of which is yet to be recognized pending the appearance of these scripts in print. It can still be said that the unique value of this contribution lies in the ability of Waheed to convert the deepest ideals of his nation into homely parables that won the hearts of eveybody as simple love stories. For instance, Sohail Rana has discussed in detail that ‘the point in Armaan‘ is the ‘transformation’ of a young man from being a convivial type of character into someone maturer (or ‘the austere type’, if we could borrow a term from the American sociologist Franklin Giddings).

In spite of this, the work of Waheed as a writer received almost no appreciation in his lifetime. Even the critics who acknowledged Armaan as a trendsetter usually credited it to direction, embellishment and music rather than the script. As mentioned in Waheed Murad: His Life and Our Times (2015):

In one of the earliest references to Armaan, which appeared in ‘Film Notes’ in Dawn soon after the release of the movie, it was said that ‘there is nothing here by way of story.’ The elements that were going to appeal to the sophisticated audience were pointed out very insightfully, and the genre correctly identified as melodrama, but surprisingly, the script was still blamed for following conventions that had long been accepted as legitimate in that genre even in Europe.

Actor

Waheed is said to have done a cameo in Saathi (1959), produced in Lahore by the family friend Darpan. However, the existing print of the movie is not good enough for ascertaining this. In any case, his first assignment as an actor was the titular role in the movie Aulad (1962). It was directed and co-produced by S. M. Yusuf, whose son Iqbal Yusuf directed and co-produced the last posthumously released movie of Waheed, Zalzala (1987). Waheed acted in 124 movies in all.

As an actor, he was known for his professional demeanor. Director Shaukat Hashmi, for instance, has written in detail how he booked Waheed for 12 shifts for the movie Doctor (1965) but Waheed’s work got completed in just 10 shifts due to his cooperation and punctuality. In an interview published in the weekly Nigar in 1973, it was reported that he was departing for the outdoor shoot of the movie Pyar Hi Pyar (1975) although he was suffering from flu at that time. Pervez Malik, however, has mentioned that misunderstandings arose between him and Waheed during the shooting of Dushman (1974) because the latter was unable to give sufficient time. However, Pervez admitted that the misunderstanding was partially due to hightened expectations on his part as an old friend.

There have been some suggestions that he lost his punctuality in his last years due to his poor health or other personal problems. This allegation, however, is contradicted by the fact that all the directors who were working with him in that period (such as Iqbal Yusuf, Jamshed Naqvi and Aslam Dar) kept booking him for one project after another. This could not have been possible if Waheed had become difficult to work with, especially if we see that other top-ranking stars of the day, such as Shabnam, Nadeem and Muhammad Ali were also involved in these projects.

Most contemporary accounts emphasize his habit of carrying books to the film shoots, and busying himself with reading while waiting for his cue. When going to out station locatins within the country, he usually travelled with family (the picture at the beginning of this section is from the location of Tum Hi Ho Mehboob Meray).

All the awards he received, except three as the producer of Armaan (1966), were for his work as actor. These included, among others, three Nigar Awards, three Graduate Awards and two PIA Academy Awards. The movies on which he received awards for acting were Heera Aur Pather (1964), Eid Mubarak (1965), Armaan, Insaniyat (1967), Andaleeb (1969), Mastana Mahi (Punjabi; 1971), Phool Mere Gulshan Ka (1974), Jab Jab Phool Khiley (1975), Shabana (1976), Awaaz (1978), Bahen Bhai (1979), Badnam (1980) and Ghairao (1981). He also received an award as best supporting actor for Aahat (1982) and a posthumous award in 1985 as best actor for Anokha Daaj (1981). See complete list of awards.

His first three assignments as actor were supporting roles and he was invariably presented as a well-mannered educated person, so that he may have felt the danger of being stereotyped. For instance, director Shaukat Hashmi later wrote that when he was looking for a hero who would look well-educated, he was told to take the newcomer Waheed. These are the traits that primarily earned him the epithet ‘chocolate-cream hero’ (apparently borrowed from the late-nineteenth century play Arms and the Man by George Bernard Shaw, where the protagonist is called ‘Chocolate Cream Soldier’ because he carries chocolate instead of ammunition). In Urdu, the title was often corrupted as ‘the chocolate hero’ or even the ‘chawklaty hero’ (also inscribed on his gravestone).

Even then, distinction needs to be made between two types of persona in his ‘well-educated’ type of characters. The first was a young man of humble resources striving to achieve material prosperity through his education, and often called upon to make some sacrifice for a higher purpose, such as family or professional integrity. His very first role, in Aulad, belonged to this type, while the best representation was perhaps in his own production, Ehsaan (1967).

The second persona was that of a young man from a wealthy background, who did not have to struggle for a career but went straight ahead on the course of self-discovery through the pains of relationship. This was his character in his second assignment, Daaman (1963), but of course the most iconic depiction of this came in Armaan, which turned him into a living legend overnight. Anjuman (1970), which he regarded as his best movie, also presented him in this kind of role.

Film critics in those days seemed to be willing to acknowledge him mainly in these two kinds of role only. This is evident from the fact that all the awards he reveived, except for Heera Aur Pather and Awaaz, were for characters that fell into one of these two classes. In those days, psychologically complex roles were usually regarded as the territory of the fellow-actor Muhammad Ali while serious roles highliting the need for social justice came to be the specility of Nadeem after his debut in 1967. In an interview to Nigar in 1973, Waheed defended his status by saying that it is no less difficult to enact a playful character with finess than other types of roles.

Even then, his eagerness to prove his versatility and his courage for innovation were discernable from the very beginning. In his very third assignment, and even before doing a lead role, he dared take up a negative character (although one who gets reformed in the end). In his interview to Mag in the last year of his life too, he tried to emphasize how he had dared to do very off-beat roles, and this is indeed true. In Sheeshay Ka Ghar (1978), he even played an outright villain. Other characters that deviated from the norm include the man-turned-woman in the burlesque, Aurat Raj; good or bad burglars in Ek Nagina, Afsana, Hill Station, Daulat Aur Duniya, Jaal, Jab Jab Phool Khiley, Parakh, Insaan Aur Shaitan, Ghairao and one of his two roles in Hero; the faithless spouse in Bahen Bhai; and the snake-turned-human in Naag Aur Nagin.

His decision to play the character of a donkey cart driver in his first lead role (in his own production Heera Aur Pather) may also have been motivated by his desire to prove his versatility. It earned him a Nigar right away. This was someone with no schooling but an indomitable will, and was followed by the roles of Waheed in such movies as Mastana Mahi (one of his double roles), Pyar Hi Pyar, Waqt, Wahda, Goonj Uthi Shehnai, Khuda Aur Mohabbat, Awaaz, Raja Ki Ayai Gi Barat and Hero (one of his double roles).

He also appeared in costume roles. The completest examples would be movies that involved almost no interaction with the contemporary mindsets and were set entirely in bygone eras, ethnic settings or fictitious sub-cultures, e.g. Joshh, Jaag Utha Insan, Samandar, Laila Majnu, Ishq Mera Naa (Punjabi), Naag Aur Nagin (already mentioned in another category) and Zaib-un-Nisa. To this list may be added the Pakistani equivalents of the genre of ‘Muslim social movie’, which was originally conceived in British India but also thrived after independence, especially in India, till the end of the twentieth century. One of the most outstanding Pakistani examples was Deedar (1974).

Further reading

This write-up is based on Waheed Murad: His Life and Our Times (2015) by Khurram Ali Shafique. The UK-US edition has been published by Libredux UK and the Pakistani edition by Akhtar Wasim Dar for Libredux Pakistan. Both can be ordered online.

Leave a Reply